----

Battle Lines Is A Civil-War Comic Hollywood Can Learn From

// The Atlantic Wire

When people think of comics they typically think of bite-sized chunks, which is one of the reasons why the medium has long been viewed as unserious and juvenile. Neither the daily strip nor the monthly superhero story has enough heft to provide deep insights into life, the universe, or anything. It's no coincidence that the works that have won mainstream acceptance, like the initially serialized Maus and Watchmen, work as longform graphic novels that can hold their own on a bookshelf next to more weighty tomes like Moby Dick or Ulysses. Big themes and big stories, conventional wisdom goes, require big works.

The Civil War is as vast a story as one can expect, but Battle Lines: A Graphic History of the Civil War doesn't attempt to do justice to it by going big. Instead, the writer and artist Jonathan Fetter-Vorm and the historian Ari Kelman organize their tale in a traditional way—as a series of separate strips punctuated with single text-pages providing historical background. Battle Lines doesn't provide one sweeping narrative, like, say, Gone With the Wind, but instead offers a series of fragmented, partial glimpses of a whole that is never summed up as a whole. In one vignette, a Southern plantation owner tries and fails to buy food on credit after her field hands leave her to escape from slavery and run north; in another gruesome sequence a photographer takes pictures of the aftermath of battle, positioning bodies and waiting for the film to expose. "This is a helluva lot easier when they're dead," the assistant quips—a glancing comment, perhaps, on the ghoulishness of art about war, and of the impulse to freeze the dead into one meaningful position.

Like the photographer, Battle Lines props up the dead for its own purposes. But its fragmentation helps it to avoid many of the standard poses in which Civil War narratives often get frozen. Thanks at least in part to the involvement of the historian Kelman, the work doesn't replicate the thoroughly discredited neo-Confederate Lost Cause myth of glorious Southerners fighting a gallant but futile fight against overwhelming Union forces. But it also doesn't create a counter-myth, as the film Lincoln does, of noble white northerners rescuing black people from oppression. Battle Lines is bracingly free of the ubiquitous scene in which a courageous white person frees black slaves from their chains, and the slaves stare tearfully up at their savior in a cathartic and melodramatic recognition of virtue.

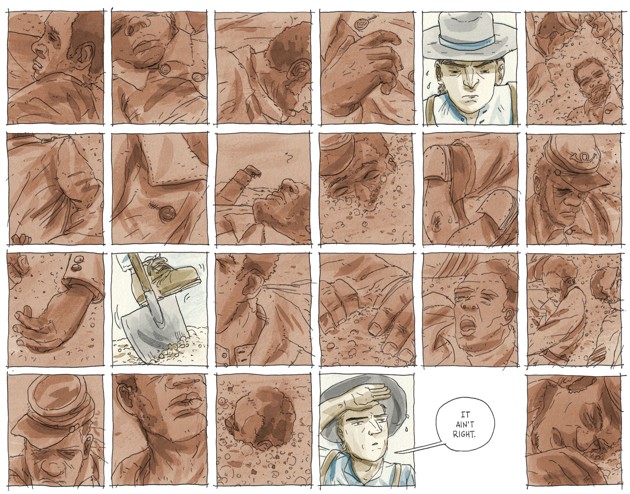

Instead, it includes a short story called "Leg Irons." In it, a black man named George Washington flees from slavery, and, still in chains, manages to get across Union lines. The story is set in 1861, before the Emancipation Proclamation, and so the status of Washington is uncertain; the Union soldiers who capture him don't send him back South, but they don't exactly free him either. Instead, they send him to a ramshackle camp for the other escapees—which is to say, he's put in a different sort of prison. The 11-page comic shows Washington hobbling across the page, Fetter-Vorm's stiff art making him look all the more awkward and vulnerable. Washington walks; some Union soldier stops him and points a gun at him. He walks again; someone stops him and points a gun at him. There's no apotheosis of freedom, just a slog from slavery toward something that's only slightly better. When Washington asks the camp registrar if his wife and child have come through, the official can't even be bothered to look in the book. In Battle Lines, the march to freedom isn't a triumphant ascent, but a shuffle in a circle. Whites, north or south, are more likely to be obstacles than saviors. Every inch gained is granted reluctantly, and may well be taken back.

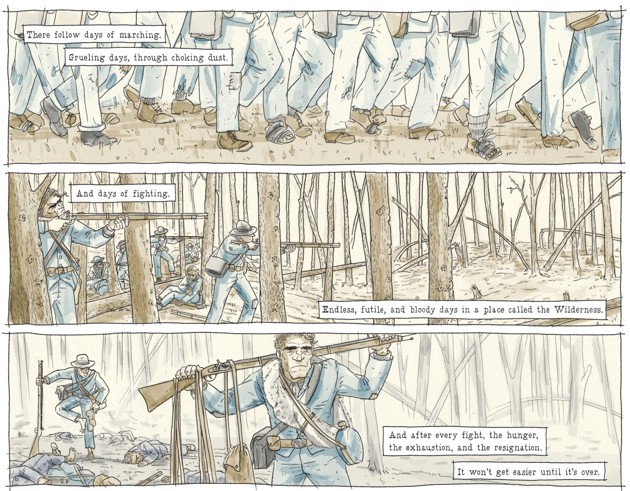

Unitary narratives about the war require unitary endings. In Hollywood, those endings are generally inspirational: The slaves are freed, the equal-rights amendments are passed, the bad guys get shot. Battle Lines, though, doesn't have any single conclusion, and so avoids the narrative drive toward uplift. There are a couple of moments of happiness and release—as when one black woman in slavery reads the Emancipation Proclamation to her husband with a look of subdued disbelief. But for the most part, war doesn't make for happy conclusions. "It shouldn't be too long, though, before Uncle Sam sees what's fair is fair and this whole matter gets settled," a black soldier writes home. He's hoping for equal pay, but the text of the letter is juxtaposed with an image that shows him already dead and buried in a shallow grave. Union prisoners at the Confederate POW camp Andersonville repeat rumors about prisoner exchanges as they grow thinner and thinner, wasting away. In a film about Andersonville, perhaps, the narrative would go on long enough for someone, at least, to be released. But here the story ends too soon—just as it did for thousands of those imprisoned there.

It's perhaps too much to expect Hollywood to learn from a work like Battle Lines. You don't invest money in a blockbuster feature film in order to put a bunch of depressing vignettes onscreen. But Kelman and Fetter-Vorm are able to work on a smaller scale because their whole project is smaller—they're aiming for classroom influence, not international success. Still, even if it's not likely to transform American cultural representations of the Civil War, the book is a useful corrective to the default, big-screen approach to history, which frames the nation's bloodiest war in terms of big, great narratives of tragedy, triumph, courage, or freedom. In Battle Lines, the Civil War is presented instead at comics size; small and broken, the parts more important than the whole.

----

Shared via my feedly reader

Sent from my iPhone

No comments:

Post a Comment