----

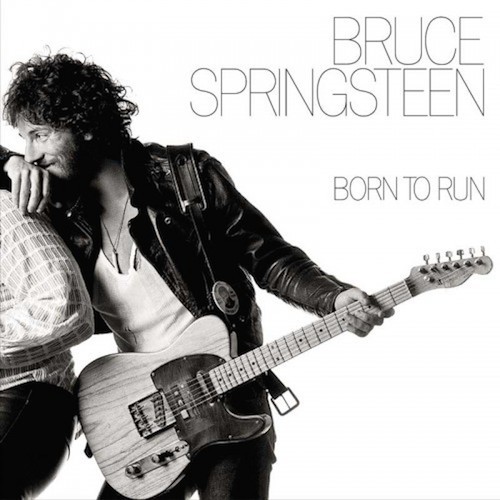

Born to Run and the Decline of the American Dream

// The Atlantic Wire

Forty years ago, on the eve of its official release, "Born to Run"—the song that propelled Bruce Springsteen into the rock-and-roll stratosphere—had already attracted a small cult following in the American rust belt.

At the time, Springsteen desperately needed a break. Despite vigorous promotion by Columbia Records, his first two albums, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle, had been commercial flops. Though his band spent virtually every waking hour either in the recording studio or on tour, their road earnings were barely enough to live on.

Sensing the need for a smash, in late 1974 Mike Appel, Bruce's manager, distributed a rough cut of "Born to Run" to select disc jockeys. Within weeks, it became an underground hit. Young people flooded record stores seeking copies of the new single, which didn't yet exist, and radio stations that hadn't been on Appel's small distribution list bombarded him with requests for the new album, which also didn't exist. In Philadelphia, demand for the title track was so strong that WFIL, the city's top-forty AM station, aired it multiple times each day. In working-class Cleveland, the DJ Kid Leo played the song religiously at 5:55 P.M each Friday afternoon on WMMS, to "officially launch the weekend." Set against the E Street Band's energetic blend of horns, keyboards, guitars and percussion, "Born to Run" was a rollicking ballad of escape, packed full of cultural references that working-class listeners recognized immediately.

The rise of Bruce Springsteen is in many ways a typical rock success story, but it also reveals a great deal about one of America's most contested eras. Since 1976, when Tom Wolfe branded the seventies as "the Me Decade," Americans have tended to write off the era as a socially and politically barren time during which millions of people descended into mindless self-absorption. Standing in sharp contrast with the turbulent '60s, the '70s seem to have given rise to a popular repudiation of the high-minded spirit evident in the civil-rights, student, and anti-war movements.

But the story of the '70s is much more complicated. Far from being an era of complacency and narcissism, the decade gave rise to social, political and cultural debates that built on and even surpassed the era of Kennedy and King. Some issues, like civil rights, the sexual revolution, and Vietnam, belonged as much to the '70s as to the '60s. Others, like feminism, abortion, gay rights, busing, the tax revolt, and Christian Right politics, seemed altogether new.

Considered in this context, Bruce Springsteen's phenomenal breakthrough in 1975 can only be understood against a backdrop of profound dislocation and urgent activism, particularly in the working-class communities that absorbed so many of the decade's economic and cultural shocks.

* * *

Reflecting on his formative years in Freehold, New Jersey, Springsteen once described the home he grew up in as a "dumpy, two-story, two-family house, next door to the gas station." Several companies had manufacturing plants there—3M, Nescafé, the odd rug mill or paper plant—but by the post-war era, the city, like so many other middling urban areas, was dying. "Freehold was just a … small, narrow-minded town," Springsteen told the English radio interviewer Roger Scott in 1984, "no different than probably any other provincial town. It was just the kind of area where it was real conservative. It was just very stagnating. There were some factories, some farms and stuff, that if you didn't go to college you ended up in. There wasn't much, you know; there wasn't that much."

Home wasn't a happy place for Springsteen, and neither was school. A loner by nature, he coasted anonymously without leaving much of a mark. At Freehold Regional High School, he played no sports, participated in no extracurricular activities, and barely passed his classes, according to the biographer Dave Marsh. "I didn't even make it to class clown," Bruce later remarked. "I had nowhere near that amount of notoriety."

Years later, as the writer Eric Alterman recounts, one of Springsteen's classmates reflected, "If he hadn't turned out to be Bruce Springsteen, would I remember him? I can't think of why I would. You have to remember, without a guitar in his hands, he had absolutely nothing to say."

Springsteen's only passion was music. He joined his first band, the Castilles, when he was still in high school. Their professional debut at the West Haven Swim Club led to a smattering of engagements at local roller-skate rinks, junior high school dances and supermarket openings.

After an unremarkable stint at Ocean County Community College, he relocated to Asbury Park, a gritty coastal community that scarcely resembled the glitzy seaside resort of its earlier days. By that time, jet travel and air conditioning had made distant locations like California, Florida, and the Caribbean more attractive to local vacationers. Deeply segregated and suffering from massive unemployment, the city erupted in violence between black rioters and a mostly white police force in July 1970, resulting in $4 million of property damage and 92 gunshot casualties. The town soon became a shadow of its former self—a half-desolate collection of small beach bungalows, decaying hotels, a modest convention center, and a handful of greasy-spoon diners.

But what it lacked in vigor and polish, Asbury Park made up for in artistic vitality. Lining its boardwalk were a motley assortment of bars where aspiring Jersey musicians like the drummer Vini Lopez, the keyboardists Danny Federici and David Sancious, the saxophonist Clarence Clemons, and the guitarist Steve Van Zandt—all of whom eventually played alongside Springsteen—forged a dynamic, interracial, and working-class rock and roll scene. The artists who eventually united under the banner of the E Street Band were revolting against the soft-pop sensibilities of acts like Donny Osmond, the Bee Gees, Chicago, America, Elton John, and the Carpenters, all of whom dominated the charts in the early '70s. Combining elements of jazz, funk, Motown and rhythm-and-blues, the various incarnations of Springsteen's bands—Child, Steel Mill, Dr. Zoom and the Sonic Boom, the Bruce Springsteen Band, and, finally, the E Street Band—enjoyed increasingly wide appeal among men and women from blue-collar families who frequented the Jersey shore music scene and who found the prevailing sound an inadequate soundtrack to their youth.

Living in a dingy apartment atop a mom-and-pop drug store, Springsteen churned out hundreds of original songs packed with the rich imagery of working-class life. According to Marsh, Springsteen later observed that he "wasn't brought up in a house where there was a lot of reading and stuff." Yet for his lack of formal education, he developed into a master wordsmith, able to capture in lyrics the experience of millions of people who were trying to find their way in the troubled 1970s.

* * *

The '70s were a punishing time for America's working-class communities. A brutal combination of commodity supply shocks, loose monetary policy, and federal deficits—the latter, a hangover effect from the Vietnam War—created both sky-high inflation and unemployment; the resulting phenomenon, which economists dubbed "stagflation," interrupted a quarter-century of seemingly boundless growth and prosperity.

Compounding these challenges, many of the well-paying industrial jobs that once lifted blue-collar workers into the ranks of the American middle class began to disappear. In Youngstown, Ohio, steel plants were shuttering their doors by mid-decade, the result of foreign competition and failure to invest in new technology. In Elizabeth, New Jersey, the slow demise of the Singer sewing-machine plant, once the mainstay of the city's economy, ushered in a period of post-industrial ruin. Sixty miles south on the New Jersey turnpike, Camden, the worldwide anchor of the Campbell Soup company, saw its manufacturing base drop from 38,900 jobs in 1948 to just 10,200 in 1982. Though each industry experienced its own, unique set of circumstances, the prevailing narrative was one of industrial decline.

Amid all this, blue-collar Americans were still reeling from the Vietnam War, a conflict that saw working-class men of all races do most of the fighting and dying. They were no less immune than anyone else to the general dissolution of authority—be it paternal, governmental or civic—that seemed everywhere on display. And they were fully implicated in the creative cultural disruption of second-wave feminism and the modern gay-rights movement. In response to the decade's turbulence, working-class communities exhibited a full range of grassroots political expression. Sometimes that activist spirit turned ugly, as with the anti-busing movement. But often, it didn't.

Between 1967 and 1977 the average number of workers on strike climbed by 30 percent and the number of work days lost to stoppages by 40 percent. "At the heart of the new mood," argued The New York Times, "there is a challenge to management's authority to run its plants." From striking postal workers in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey to the United Auto Workers' dramatic walkout against General Motors in 1970, blue-collar Americans demonstrated a degree of militancy unseen since the end of World War II.

Speaking to the grassroots labor engagement that pulsed through America in the '70s, a UAW official observed that "it's a different generation of workingmen. None of these guys came over from the old country poor and starving, grateful for any job they could get. None of them have been through a depression. They've been exposed—at least through television—to all the youth movements of the last ten years…They're just not going to swallow the same kind of treatment their fathers did ... They want more than just a job for 30 years."

Workers didn't limit their opposition to management. Often, they turned their sites on union leadership. The decade gave rise to unlikely heroes like Ed Sadlowski, the 38-year-old director of the United Steel Workers' largest district (encompassing Chicago, Illinois and Gary, Indiana) who ran as a reform candidate for the presidency of his union's international chapter. His fellow workers called him "Oilcan Eddie." Rolling Stone Magazine dubbed him an "old-fashioned hero of the new working class."

Running on a multi-racial, multi-ethnic ticket, Sadlowski lost to the union's establishment candidate by a convincing margin, but his brash style and willingness to acknowledge the drudgery associated with industrial labor played better than expected. His coalition—young, integrated, and restive—resembled nothing so much as Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band.

In the opening lines of "Born to Run," Springsteen invoked one of his favorite metaphors—the automobile as an engine of escape from the many dead ends and disappointments that seemed to constrain young, working-class Americans. "In the day we sweat it out in the streets of a runaway American dream / At night we ride through mansions of glory in suicide machines / Sprung from cages out on highway 9 / Chrome wheeled, fuel injected and steppin' out over the line / Baby this town rips the bones from your back / It's a death trap, it's a suicide rap / We gotta get out while we're young." It was a fitting emblem for its time.

* * *

By the mid-seventies, Springsteen was widely hailed as a "rock 'n' roll poet—someone who had "watched the crowds pass down the street, observed the hookers, the pushers, experienced the loose girls on the block and yet managed to keep just far enough away to keep out of major trouble," in the words of the Bucks County (PA) Courier Times. He radiated working-class authenticity. His songs "contain lyrics guaranteed to blow you away," wrote a critic for the Syracuse Post-Standard, "telling of tenements, back alleys, greasers, pimps, jukeboxes, 'switchblade lovers,' 'romantic young boys' and 'Billy,' who's 'down by the railroad tracks, sitting low in the back seat of his Cadillac.'"

Lester Bangs, Rolling Stone's highly influential rock critic, was an instant fan. "Hot damn, what a passel o' verbiage!" he crowed. Some of his lyrics "can mean something, socially or otherwise, but there's plenty of 'em that don't even pretend to."

On October 27, 1975, both Time and Newsweek featured Springsteen on their covers, with Time hailing him as a "glorified gutter rat from a dying New Jersey resort town." Praising his album as a "regeneration, a renewal of rock," the magazine approvingly characterized Springsteen's music, in his own words, as being principally concerned with "survival, how to make it through the next day." Given the state of the country in October 1975—other topics that concerned Time that week included two assassination attempts on President Gerald Ford, New York City's fiscal crisis, and the persistent after-shocks of Watergate—survival struck the editors as a noble enough goal on its own terms.

Newsweek disagreed. The magazine argued that Springsteen was a creature of his record label, which had launched a $250,000 promotional campaign for Born To Run. Indeed, not everyone was buying the hype. "Springsteen is said to be a new Bob Dylan," quipped the syndicated columnist Mike Royko. "Bob Dylan was said to be a new Woody Guthrie. Woody Guthrie was a not a new anybody. He was just Woody Guthrie. I guess that's why he's never going to be as big a star as Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen."

Springsteen's critics misread his appeal. Absent from their analysis was class. The young heroes in "Thunder Road" and "Born to Run" are in flight from a very specific condition. Marsh recounts an interview in which Bruce explained, "I know what it's like not to be able to do what you want to do, because when I go home, that's what I see. It's not fun, it's no joke. I see my sister and her husband. They're living the lives of my parents in a certain kind of way. They got kids; they're working hard. These are people, you can see something in their eyes ... I asked my sister, 'What do you do for fun?' 'I don't have any fun,' she says. She wasn't kidding."

When Kid Leo played "Born to Run" at 5:55 each Friday afternoon to "kick off the weekend," he was offering musical escape. In "Thunder Road," the narrator begs Mary to "roll down the window and let the wind blow back your hair/ Well the night's busting open/ These two lanes will take us anywhere/ We got one last chance to make it real/ To trade in these wings on some wheels." With 16 percent of non-college educated youth either unemployed or underemployed, and many of their more fortunate peers awaiting the next round of layoffs or cutbacks, the flight in Springsteen's music had special resonance.

Shortly after Born to Run was released, Springsteen became embroiled in a highly public lawsuit with Mike Appel, his manager, who, in addition to demanding an excessive portion of his profits, badly mismanaged his concert and recording revenues. Only after the two parties reached a settlement in 1977 were Bruce and the E Street Band clear to return to lay down their next record. The product of their labors, Darkness On the Edge of Town, was released in 1978 to critical acclaim, followed by another best-selling record, The River, in 1980.

Both LPs revisited many of the same themes introduced in Born to Run. Rolling Stone called The River "a contemporary, New Jersey version of The Grapes of Wrath, with the Tom Joad/Henry Fonda figure—nowadays no longer able to draw on the solidarity of family—driving a stolen car through a neon Dust Bowl." But what made the album "really special" was:

[Its] epic exploration of the second acts of American lives. Because he realizes that most of our todays are the tragicomic sum of a scattered series of yesterdays that had once hoped to become better tomorrows, he can fuse past and present, desire and destiny, laughter and longing, and have death or glory emerge as more than just another story.

* * *

To appreciate Bruce Springsteen's social and political bent, it's helpful to compare Born to Run to the competition. As popular as that album was, for millions of Americans who came of age in the 1970s, it was James Taylor, the six-foot-three, long-haired son of a wealthy North Carolina doctor, who supplied the decade's soundtrack. With his sad eyes and brooding stare, Taylor captured the melancholy disposition of a country still reeling from the sixties

Released in 1970, his second album, Sweet Baby James—the one that made him famous—sold 1.6 million copies in just one year. Like his fellow singer-songwriters of the seventies, a talented and varied group that included Carol King, Joni Mitchell, Jim Croce, and John Denver, Taylor was interested in the mysteries of the self. "What all of them seem to want most," Time noted, "is an intimate mixture of lyricism and personal expression—the often exquisitely melodic reflections of a private 'I.'"

Over the years, Taylor would give generously of his time and talent, appearing on stage to support liberal causes and political candidates. But social and economic concerns rarely seeped into his seventies-era compositions. There was too much personal ground to cover. Time noted that "like so many other troubled, dislocated young Americans, Taylor may at first seem self-indulgent in his woe. What he has endured and sings about, with much restraint and dignity, are mainly 'head' problems, those pains that a lavish quota of middle-class advantages—plenty of money, a loving family, good schools, health, charm and talent—do not seem to prevent." What was true of Taylor was also true of the era's most successful singer-songwriters – from Carol King and Joni Mitchell, to Billy Joel and Jim Croce.

Critics of this new genre of songs about the self (known also as "I-rock") risked glorifying earlier generations of musicians. Indeed, there was nothing especially political about the better part of the American songbook that predated the seventies. Those who longed for a more meaningful past would have strained to find deeper meaning in the bubble-gum pop of the early and mid-sixties. Even Bob Dylan eschewed most political themes after 1963, at least on the surface. But there was a distinction between the singer-songwriters and rock balladeers like Bruce Springsteen. Singer-songwriters represented the inward turn that we most popularly associate with the seventies—a very real phenomenon with authentic cultural resonance. By contrast, Springsteen embodied the lost seventies—the tense, political, working-class rejection of America's limitations.

* * *

Lost amid popular memories of kitsch—of waterbeds and pet rocks, mood rings and self-help books—is the story of a more complicated decade. The enduring sway of Born to Run isn't just thanks to the music, which stands up strongly, four decades later. It stems also from the unique time and place in which Americans first came to know Bruce Springsteen.

An intensely private figure, Springsteen rarely sat for interviews, particularly in the early years. But when he did, politics was never far from his mind. "I don't think the American Dream was that everyone was going to make it or that everyone was going to make a billion dollars," he later said (as captured in the anthology, Bruce Springsteen Talking). "But it was that everyone was going to have an opportunity and the chance to live a life with some decency and a chance for some self-respect."

It's been forty years since "Born to Run" first captivated the popular imagination. In many ways, we're living in a comparatively prosperous decade: Downtown Freehold has been restored to its original splendor, and the Asbury Park boardwalk is lined with upscale bars and restaurants catering to an upwardly mobile crowd. Yet Americans still grapple with the same concerns that animated a young Bruce Springsteen. The place and condition of one's birth continue to define the outer boundaries of possibility. All of which makes the music as meaningful as it ever was.

----

Shared via my feedly reader

Sent from my iPhone

No comments:

Post a Comment